I’ve been thinking about saying something on this topic for a while. I held off because it’s going to make people even more angry, but I was talking to an old photographer about this issue today and I figured I may as well go for it. Grab your precious EF mount lenses and your pitchforks, because this is where I drop a stinker on the Holy Grail of Cameras™, the full-frame video camera (and APS-C and medium format while I’m at it.)

Cameras with larger sensors are a real pain in the ass. I’m sure the number one thing that rushes to your mind as you try to predict my complaints and plan your angry retorts is the size of a full-frame camera, and that’s definitely true: the larger your sensor, the larger the camera body has to be. There’s no way around that fact. It’s a big sensor and it needs a lot more in the way of life support than a tiny sensor. Unfortunately, the size issue extends far beyond the camera body itself.

I mean FAR BEYOND THE CAMERA.

The lenses shown above are wide-aperture super telephoto primes and the first relatively close (in 35mm equivalent focal length) I could find photos of in a person’s hands. The top lens is a cannon of a lens (pun totally intended) on a Canon full-frame camera; the bottom is an Olympus pro lens on a micro four-thirds camera. Notice how the entire Olympus lens would fit in the area between the Canon lens support on the tripod and the Canon body. The Olympus is a 100mm longer lens in 35mm equivalence, too. In fact, the only area in which the Olympus is “inferior” is producing a shallow depth of field at f/4. Because the micro four-thirds sensor is one quarter of the size of a full-frame sensor (which results in a crop factor of 2.0), the optics don’t have to be nearly as big to achieve the same subject framing and gather the same amount of light, but the fact is that a 300mm focal length is not 600mm and doesn’t work like 600mm; that’s just the 2.0x crop making it work that way, but all the calculations for depth of field will still work based on the true 300mm focal length.

Side note: many people incorrectly apply the crop factor to the f-number (aperture) value as well, but the crop factor doesn’t affect the way an f-number is calculated. The f-number is based on the size of the lens entrance pupil and the lens focal length, neither of which are affected by a sensor’s crop factor. Only apply crop factor to depth of field calculations and perceived amount of image noise.

The big sensor also comes with a big appetite. Larger sensors require more power, generate more heat, and (mostly due to higher megapixel counts) need more powerful image processors in the camera which means even more power and heat. That’s why a full-frame camera battery is bigger than many small-sensor camera batteries, yet can’t shoot as long. There is also a higher risk of the sensor overheating; some Sony full-frame mirrorless cameras are notorious for such overheating issues causing surprise shutdowns in the middle of shooting.

In short, cameras with bigger sensors require more money, more space, more strength and stamina to lug around and use, more power, are at higher risk of overheating. But would you believe that none of these things is my main problem with large-sensor cameras? It’s true. For the improved color quality and reduced noise, I can think of several situations where I would gladly work around all the weight issues and insanely high cost of bodies and lenses and terrible battery life. You can buy more batteries, and what are tripods for if not to hold your weapon of a full-frame camera? So if all of this isn’t what inspired me to write a lengthy article, what in the world is so bad that I’d rattle off this much text over it? Well, it’s simple:

Shallow depth of field sucks.

Look, I understand. I got a Canon T1i in 2010 and it was my first good camera. Before that, I lived in a photography world consisting of a tiny-sensor cheapo Polaroid i1036 point-and-shoot and whatever low-resolution camera phone I had at the time. Getting an APS-C DSLR was a mind-blowing experience, and having someone come over that also shot on Canon and offered to teach me and wielded the One True Lens, the famous “nifty-fifty” EF 50mm f/1.8, I was like a child visiting a huge candy store for the first time. I’d love to share my personal experiences with the often troublesome tool that is shallow depth of field. A picture is worth a thousand words, so…

A visual tour of discovering shallow depth of field

Proof (finally) that shallow depth of field sucks!

As most photographers (and videographers) tend to do, I eventually learned about stopping down for sharpness and for getting a deeper acceptable focus depth. It took a while for me to come around and realize that shallow depth of field is more likely to be a bad thing than a good thing. For portrait photography, a wide-aperture long telephoto lens is the epitome of awesomeness, but almost everything else needs more overall focus in the image.

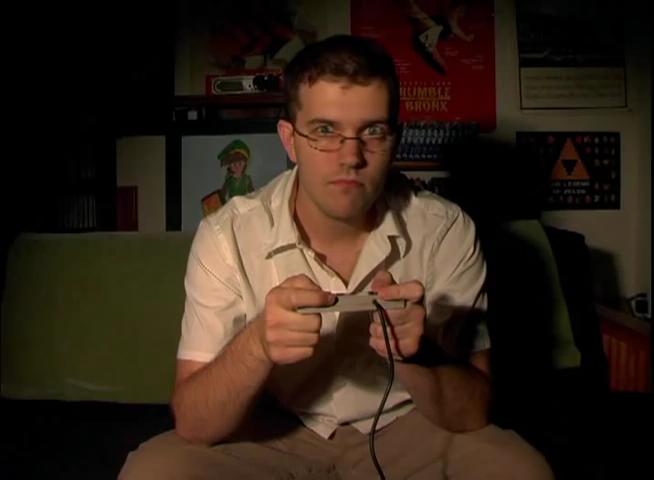

The big epiphany hit me when I was replaying old episodes of Angry Video Game Nerd and bouncing around in the episode list a lot. I happened to jump between a few episodes where he changed his camera setup. From what I understand, James Rolfe used a Panasonic DVX100 camcorder with MiniDV tapes for a very long time, and the DVX100 uses a 1/3″ 3CCD sensor system. He upgraded to an HVX200 which used the same sensor system, then when he got the money for his movie he seems to have gotten something a little better with full HD (P2 cards for the HVX, maybe?) and then jumped up to something expensive with an obviously huge sensor. His video quality evolved, too: he went widescreen and then went full-frame widescreen. Unfortunately, I found that there was something wrong with the newer episodes that made them far less appealing to me, and it wasn’t just the somewhat more forced acting. Something bothered me, but I couldn’t pinpoint it. Maybe you can come to the same epiphany if you study the following three images which are in chronological order:

Do you see why the last one is worse than the other two? Take a long, hard look, then read on.

Backgrounds (and foregrounds) are important.

The third shot is worse because of the shallow depth of field. Until I saw these videos in the same watch session, I didn’t realize what was going on, but it stands out like a sore thumb ever since I noticed. The tiny sensors of the Panasonic MiniDV camcorders have a really large focus depth compared to a full-frame camera set up to take an identical shot at the same distance. You can very clearly read the “RUMBLE IN THE BRONX” poster behind him in the first shot, plus all of the other posters are about as clear as the lighting can make them. In the second shot, it’s the same story: you can see the mini arcade games, the cartridge boxes and end labels, and if you had a copy of the full 1920×1080 screenshot, you’d be able to make out the text on most of the end labels. The wall of stuff behind him is super important because it’s part of his character. Seeing game posters and games enhances the authentic feeling that the setting grants to the character.

And then there’s that third shot. That third, high-quality, shallow as hell shot. The games are unreadable. The boxes are unreadable. The colors mush together. Everything is so out of focus that it all blends into a mish-mash of “this stuff doesn’t matter.” Ironically, as the visual quality of the character experienced a meteoric rise, the perceptual quality of the show declined because the background that is an integral part of the character was rendered useless. This change first happened in AVGN episode 109, “Atari Sports,” and it never stopped. In a way, I should be grateful that this change happened. I grew a new and very powerful appreciation for the importance of backgrounds in photography and filmmaking.

Here are a few screenshots from one of my favorite films, Swing Girls (2004). Imagine how they would look with the backgrounds (and foregrounds!) lost to blurry out-of-focus swirls of bokeh, and how they’d have to be shot differently if the depth of field was a lot shallower. (Yes, this was shot on film, but the concepts behind depth of field and acceptable focus work the same way. Remember that Super 35mm film has a roughly APS-C sized frame; full-frame is significantly larger.)

Having the out-of-focus bits too far out of focus would have ruined these scenes. Being able to see what’s in a room or what other people are doing, even if not the main subject in the frame, is a crucial tool in visual storytelling. That’s not to say that they didn’t use some shallow depth of field effects…

With large-sensor cameras, it’s hard to achieve a deep depth of field without heavily boosting the ISO (or gain) which means adding a lot more noise to the image. The other alternative is having tons of lighting on hand, something which might be an option if you have a decently large budget and a heavily controlled environment to shoot within. For the rest of us, smaller sensors give great visual results that suit most of the stories we want to tell with far less effort than their full-frame counterparts. There are certainly some situations where the advantages of a large sensor can outweigh the negatives, particularly portrait-style shots and focus racking shots, but for everything else it just makes sense to stick to cameras with smaller sensors.

Don’t give in to the hype. Each tool has its purpose. Full-frame cameras are a useful tool, but they are all too often idolized. You may really be better off with that cheaper mirrorless camera over that crazy expensive full-frame beast that your filmmaking peers are all swooning over.

100% agreed.